Anaemia, a condition signified by a marked deficiency of red blood cells or hemoglobin, has a profound impact on the body’s ability to oxygenate tissues and organs. This common blood disorder can arise from a diverse array of issues, including iron deficiency, chronic diseases, or nutritional deficits, making its diagnosis and treatment paramount for those affected.

To arm readers with essential knowledge, this article provides a comprehensive step-by-step guide to the diagnosis and management of anaemia. It will delve into the causes, unpack the variety of symptoms, and elucidate the different types of anaemia, including pernicious and aplastic anaemia, as well as dietary considerations like iron-rich foods, offering a clear pathway to improved health for individuals grappling with this condition.

Table of Contents

ToggleUnderstanding Anaemia

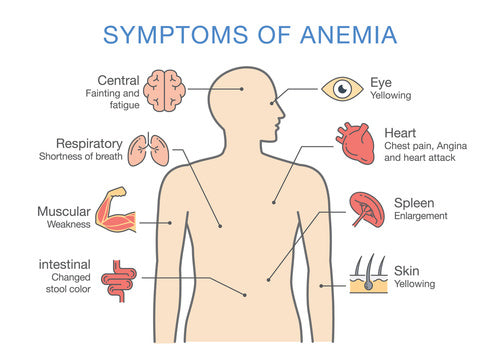

Anemia is a pervasive blood disorder affecting approximately 3 million Americans, manifesting in symptoms that can significantly impair daily functioning. These symptoms include:

- Weakness and Fatigue: A common manifestation due to the insufficient oxygenation of tissues.

- Respiratory Symptoms: Shortness of breath and a fast or irregular heartbeat are indicative of the body’s attempt to compensate for reduced oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Neurological Symptoms: Dizziness, headaches, and a pounding sensation in the ears may occur as the brain receives less oxygen.

- Physical Signs: Cold hands and feet, along with pale or yellowish skin, are visible cues of anemia. In severe cases, chest pain may arise, signaling potential heart strain.

The pathophysiology of anemia involves three primary mechanisms:

Decreased Production: This can occur due to a deficiency in essential nutrients like iron, folate, or vitamin B12, or from bone marrow disorders.

Increased Destruction: Certain conditions lead to premature destruction of red blood cells, as seen in sickle cell anemia.

Blood Loss: Chronic or acute bleeding, often from the gastrointestinal tract, can deplete the body’s red blood cell count.

The intricate process of red blood cell formation is a 21-day journey beginning with a pluripotent stem cell, which eventually matures into a reticulocyte. The kidneys play a crucial role by producing erythropoietin, which stimulates this transformation in the bone marrow. Understanding these processes is essential in comprehending how different types of anemia, such as iron deficiency, pernicious anemia, and aplastic anemia, develop and impact the body.

Common Causes of Anaemia

The common causes of anemia can be broadly divided into three categories:

Blood Loss:

- Gastrointestinal conditions such as ulcers, hemorrhoids, gastritis, and cancer can lead to chronic bleeding.

- The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may contribute to stomach bleeding.

- Menstruation and childbirth are significant sources of blood loss in women.

- Trauma or surgery can result in acute blood loss.

Decreased or Faulty Red Blood Cell Production:

- Iron deficiency is the most prevalent cause, potentially due to blood loss, poor dietary iron intake, or increased demand during pregnancy or growth periods.

- Vitamin deficiencies, particularly B12 and folate, can lead to megaloblastic anemia, where red blood cells are not produced correctly.

- Bone marrow and stem cell problems, including aplastic anemia, can halt red blood cell production, often triggered by external factors like radiation, chemicals, or certain medications.

- Inherited conditions like sickle cell anemia affect hemoglobin structure, leading to faulty red blood cells.

Destruction of Red Blood Cells:

- Hemolytic anemia occurs when red blood cells are destroyed faster than they can be made, due to factors like autoimmune disorders, infections, toxins, or inherited conditions.

- Mechanical destruction of red blood cells can happen due to an abnormality in the blood vessels or the heart.

Furthermore, anemia can be a secondary condition resulting from other illnesses such as kidney disease, which affects erythropoietin production, or cancer treatments that impair bone marrow function. Understanding these causes is crucial for targeted treatment and management of anemia, ensuring that interventions are tailored to address the underlying issue, whether it be supplementing deficient nutrients or treating an associated chronic condition.

Read : Vegetarian Diet? Discover the Best Vitamin B12 Rich Foods

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Recognizing the symptoms of anemia is crucial for timely diagnosis and treatment. These symptoms may range from mild to severe and include:

Fatigue and weakness, often the first signs, due to insufficient oxygen delivery to tissues.

Shortness of breath, dizziness, and lightheadedness, especially with activity or upon standing, indicating the body’s struggle to oxygenate efficiently.

Pallor or jaundice of the skin, and the appearance of a blue color to the whites of the eyes, visible indicators of anemia.

Tachycardia (rapid heartbeat) and palpitations, as the heart attempts to compensate for the reduced oxygen-carrying capacity.

Headaches, chest pain, and cold distal extremities (hands and feet), further reflecting the systemic impact of anemia.

More severe symptoms can include brittle nails, mouth ulcers, loss of sexual interest, increased menstrual bleeding, an inflamed or sore tongue, pica syndrome (craving for non-nutritive substances), and growth problems in children.

Diagnosis of anemia is a multi-step process involving:

Medical History and Physical Exam: A thorough review of symptoms, family history, and a physical examination to detect signs such as pallor and jaundice.

Blood Tests: These are critical for confirming anemia and include:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Measures the number, size, volume, and hemoglobin content of red blood cells, and calculates the mean corpuscular volume (MCV).

- Reticulocyte Count: Assesses the rate of production of new red blood cells.

- Iron Profile: Includes blood iron levels and ferritin levels to evaluate iron stores.

- Vitamin B12 and Folate Levels: To identify deficiencies that may cause megaloblastic anemia.

- Additional Tests: Depending on the suspected cause, tests like hemoglobin electrophoresis, liver function tests (LFT), or bone marrow analysis may be necessary.

Interpreting Results: Hemoglobin values considered indicative of anemia vary by age, gender, and ethnicity. For example, according to WHO criteria, anemia is diagnosed when hemoglobin levels are less than 12 g/dl in premenopausal females and 13 g/dl in postmenopausal females and males.

It is important to note that diagnostic criteria may differ; for instance, the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPTF) has specific guidelines for screening children for iron deficiency anemia. Furthermore, epidemiological reporting of anemia may vary, with different criteria used in the United States compared to the WHO standards.

Types of Anaemia

Anemia can manifest in various forms, each with distinct causes and implications for treatment. Understanding the types of anemia is critical for effective management:

Microcytic Anemias: Characterized by red blood cells that are smaller than normal due to insufficient hemoglobin. Key conditions include:

- Iron-deficiency anemia: Often stemming from dietary iron deficiency or blood loss.

- Sideroblastic anemia: Abnormal accumulation of iron in red blood cells.

- Thalassemia: A genetic disorder causing abnormal hemoglobin production.

- Lead toxicity: Exposure to lead disrupting red blood cell synthesis.

Normocytic Anemias: These involve red blood cells that are normal in size but reduced in number, frequently linked to chronic diseases. Examples are:

- Anemia of Chronic Disease (ACD): Typically associated with long-term medical conditions.

- Blood loss: Acute or chronic loss leading to a decreased red blood cell count.

- Hemolytic anemia: Premature destruction of red blood cells.

- Aplastic anemia: Bone marrow failure to produce sufficient blood cells.

- Bone marrow infiltrative disorders: Abnormal cells or fibers invading the marrow.

Macrocytic Anemias: These are caused by red blood cells that are larger than normal, and are divided into:

- Megaloblastic anemia: Resulting from deficiency of vitamin B12 or folate, crucial for DNA synthesis in red blood cell production.

- Nonmegaloblastic anemia: Large red blood cells without DNA synthesis problems.

Other notable forms of anemia include:

- Aplastic Anemia: Stem cells in the bone marrow are damaged, leading to a deficiency of all blood cell types.

- Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS): Dysfunctional bone marrow produces inadequate or defective blood cells.

- Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia: The immune system mistakenly destroys red blood cells.

- Congenital Dyserythropoietic Anemia (CDA): A rare inherited condition affecting red blood cell development.

- Diamond-Blackfan Anemia: A rare blood disorder where the bone marrow fails to produce enough red blood cells.

- Megaloblastic Anemia: Typically caused by vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, leading to the production of abnormally large red blood cells.

Each type of anemia requires a specific diagnostic approach to identify the underlying cause, which is essential for selecting the appropriate treatment strategy.

Treatment and Management

Treatment strategies for anemia are multifaceted, focusing on the underlying cause and the type of anemia diagnosed. The following points outline the primary treatments and management approaches:

Iron Deficiency Anaemia:

- Oral iron supplementation is typically the first line of treatment, with the aim of replenishing iron stores and resolving anemia symptoms.

- Intravenous iron may be necessary when oral absorption is inadequate or when rapid replenishment is required.

- Investigation to identify the source of iron loss is critical to prevent recurrence, addressing issues such as gastrointestinal bleeding.

Vitamin Deficiency Anemias:

- B12 deficiency anemia often necessitates vitamin B12 injections or high-dose oral supplements to restore normal function.

- Folic acid supplements are prescribed for folate deficiency, with dietary adjustments to include folate-rich foods.

Anemia of Chronic Disease:

- Managing the underlying chronic condition is paramount, which may involve a combination of medications and therapeutic strategies.

- Erythropoietin-stimulating agents are sometimes used to encourage red blood cell production.

For more severe cases or specific types of anemia, the following interventions may be required:

Blood Transfusions:

- Used to quickly increase red blood cell counts, especially in cases of severe anemia or acute blood loss.

- Risks such as transfusion reactions are considered, with erythropoietin sometimes used to reduce the need for transfusions.

Bone Marrow Transplants:

- Considered for conditions like aplastic anemia, where the bone marrow’s ability to produce blood cells is compromised.

- The procedure carries risks, including graft-versus-host disease, and requires a long recovery period.

Surgical Interventions:

- Surgery may be necessary to rectify the cause of anemia, such as repairing a bleeding ulcer or removing a part of the colon responsible for chronic blood loss.

Preventative measures and dietary management play a crucial role in both preventing and managing anemia:

Dietary Management:

- Consuming a well-balanced diet with iron-rich foods like beef, leafy greens, and fortified cereals.

- Including vitamin B12 sources such as dairy and meat, and folate from citrus juices and legumes.

Enhancing Iron Absorption:

- Improving iron absorption by reducing the intake of substances that hinder it, such as caffeine and certain types of tea.

Multivitamins:

- Older adults and individuals at risk may benefit from daily multivitamin supplements to prevent deficiency.

The management of anaemia is a dynamic process that requires regular monitoring and adjustments based on the individual’s response to treatment and changes in their condition. It is essential for individuals with anemia to work closely with their healthcare provider to ensure the most effective treatment plan is in place.

Conclusion

As we’ve explored throughout this article, anaemia presents a complex tapestry of symptoms and types, each requiring a nuanced approach to diagnosis and management. The journey from the first signs of weakness and fatigue to a thorough assessment and tailored treatment plan underscores the critical nature of understanding this condition. Through diligent application of dietary management, supplementation, and when necessary, medical intervention, individuals can navigate the often-daunting path toward restoring their blood’s vital capacity to oxygenate the body efficiently.

FAQs

Q: What are the steps to overcome anemia?

A: Overcoming anemia typically involves iron supplementation to correct iron deficiency. In some cases, further testing or treatment may be required, particularly if internal bleeding is suspected by a healthcare provider.

Q: What is the process for diagnosing and treating anemia?

A: Anemia is diagnosed through blood tests that determine the type and cause of anemia. Imaging tests may also be utilized occasionally. Treatment for anemia varies greatly depending on the cause and may include monitoring, iron supplements, medications, surgical interventions, or cancer therapy.

Q: Is it possible to detect anemia on my own?

A: While you can look out for symptoms of iron deficiency anemia, such as brittle nails, pale skin, mouth corner cracks, chest pain, fatigue, headaches, pica (craving for non-food items), and shortness of breath, a proper diagnosis should be confirmed by a healthcare professional.

Q: Can I manage anemia on my own?

A: Self-management of iron deficiency anemia can involve dietary changes if your diet contributes to the condition. Consuming iron-rich foods such as dark-green leafy vegetables, watercress, curly kale, and iron-fortified cereals and bread can be beneficial. However, it is important to consult with a General Practitioner (GP) for personalized advice and treatment.